Many we know by name.

Others we can make some educated guesses to find.

In my research, I have seen claims that the Underground Railroad was a poorly coordinated effort we just don’t know much about today.

Yet, the more I look, the more I find proving otherwise.

If it was so badly run, how did estimates exceeding 100,000 people successfully travel to freedom on it?

So, let’s talk about some of the people running it, the conductors.

I’ll start with the most obvious conductor, Harriet Tubman.

Despite what many of us learned in school, the Underground Railroad was not her brainchild, and she did not independently run it.

She used the already established Underground Railroad to escape bondage in the 1840s before her harrowing journeys leading others out of slavery.

I should start with what the Underground Railroad actually was, because if you learned it was one lady leading groups on foot through the forest, trying to get to any northern state to escape slavery, your miseducation was as good as mine.

Let’s fix this.

The Underground Railroad was an international network spanning from the British Caribbean islands and Mexico, through the Confederate States of America (which it predated), the United States, and up to Canada.

Let’s pause here, because I heard you exclaim “Canada?!” “British Caribbean?!” “Mexico?!”

I said what I said.

Particularly after the Fugitive Slave Act, it was no longer safe for anyone, even those in a free state, to help a freedom seeker.

So, the effort went international.

The Fugitive Slave Act said if you escaped slavery, a commissioned slave catcher, who gets paid by the head, could find and return you to your slaver.

Even if you reached a free state.

And anyone that aided you went down with you.

Ergo, the Underground Railroad strengthened its ties with Canada, which abolished slavery in 1833.

It also had routes passing through Florida to the coast. Freedom seekers were smuggled onto boats to the British Caribbean islands where slavery had been abolished. People connected to the cause awaited “cargo” on the islands to help them settle.

Many conductors along this part of the Underground Railroad were Native Americans, chiefly Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole.

That story again: People with a long history of fighting overreaching Europeans found solidarity with freedom seekers escaping the same folks.

Once passengers made it to the docks, black dock workers and sailors helped smuggle them aboard ships bound for free lands.

As for Mexico, they abolished slavery in 1829. Conductors along the Rio Grande were Mexican Americans and biracial couples that helped passengers get through Texas and escape to Mexico. Once again, “engineers” were ready on the Mexican side to help arrivals start their new lives.

Passengers moved along the pathways of the Underground Railroad many different ways.

Some traveled on foot through a series of safe houses.

Some traveled by wagon, on ships, aboard trains, in cases, boxes, even in coffins.

Another route out of Dixie was to make a break for it whenever the Union Army passed, then roll northward under their protection.

Now, back on track.

For conductors, we’ve got General Tubman working the northeast coast, a selection of Native Americans in the southeast, some Mexican Americans in the southwest, and some black sailors and dock workers at the ports. Do we know about any others?

Yes. Myriad.

Here’s a few more we know by name.

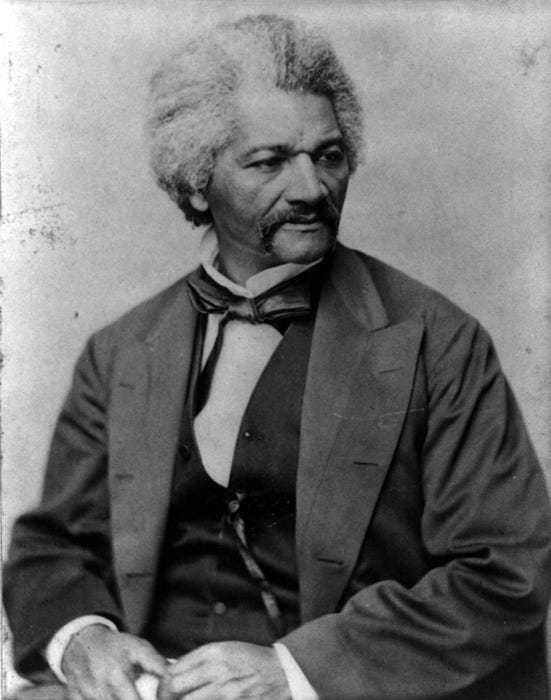

Frederick Douglas

Douglas’ first encounter with the Underground Railroad was likely when he worked in the Baltimore shipyards. His route on the Railroad involved acquiring a uniform, disguising himself as a free black sailor, and catching a train to New York. Later, he ran a waystation in Rochester that was four miles south of Kelsey’s Landing, the final stop before the shores of Lake Ontario that granted passage to Canada.

Henrietta S. Bowers Duterte

Born free in Philadelphia, Duterte was our nation’s first female undertaker. She used her profession as a cover to help the Underground Railroad. She was known to hide passengers in coffins or disguise them as part of funeral processions to get them safely through the city.

Matilda Joslyn Gage

You might recognize this name from a prior post. Her involvement in the Underground Railroad began as a tot. Her father was Dr. Hezekiah Joslyn, and the family home she grew up in was a waystation on the Underground Railroad. Her work in safehouses and abolition continued into her adult life.

John Brown

The man, the myth, the besmirched legend.

He’s a highly misunderstood historical figure since the smear campaign made it into most history books.

Brown was also raised in an abolitionist family and continued the work as an adult. Like Douglas and Gage, he opened his home as a waystation. As a conductor, Brown traveled to auctions under the guise of his wool trade and helped transport people around the country in his wagon. With the ability to travel and run a business, Brown cast a wide net that spanned many states. Even his warehouse was a waystation.

William Still

Still also opened his home as a waystation. He carefully documented his work with the Underground Railroad and the people he helped, leading to his publishing a book about it, The Underground Railroad, in 1872.

Frances Seward

The name might ring a bell, she was married to Lincoln’s Secretary of State, William Seward. While William was traveling for his political work, Frances opened up their home as a waystation and made a name for herself to freedom seekers. A newspaper article from 1891 read “it is said that the old kitchen was one of the most popular stations on the Underground Railroad, and that many a poor slave who fled by this route to Canada carried to his grave the remembrance of its warmth and cheer.”

Harriet Beecher Stowe

The author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin was speaking from a bit of experience. The Stowe’s home was a waystation, and Stowe drew inspiration for her novel from her interactions with passengers.

History provides far more confirmed conductors of the Underground Railroad than I have listed here, and plenty more I personally suspect.

For example, Clara Barton, the founder of the American Red Cross, traveled around the country as a nurse for the Union Army. Her mentor was Frances D B Gage, a leading figure in the abolitionist and feminist movements. With Frances, she taught at a school for recently emancipated students. She had access to so many people, so many places, and had her own wagon.

Was she a conductor?

You do the math. But no credible source has said as much.

We know many names, but we’ll never know them all.

Many who escaped on the Underground Railroad then turned around and joined on the engineering side to help others follow them out. The genius of the system was that it was covert, yet many elements were hidden in plain sight. Which starts me on my next topic. The Underground Railroad, Part 2 How did they communicate?